A sarabande is a dance of Spanish origins dating back to the 1500s. It is the title of Tom's poem, which I will be saving forever because it references my attention-getting fall at the arboretum and my aspirations to become a tattoo artist. Thank you, Mr. C.

We were tres heureux (so there, all you language droppers) to welcome Stacy back after a long hiatus. She has new curly hair and brought a very good poem. Brief, in lines and words. Wave - "frozen in an impossible arc of time". Nice.

Jim was here - is soccer season over? - with a political statement about living in the suburbs (of Delmar). Included some good rhymes and a few bad ones which can be easily fixed. Tim, by the way, thought Midas was only a muffler shop, but I won't laugh because he brought me a beautiful sweatshirt jacket from Cape Cod and I love him.

Tim's poem oozed sensuality with his description of men playing baseball. It was so rich in detail we marveled that he could have observed so much during a traffic stop. Thought it might be tightened up by the elimination of the fourth verse; Stacy suggested expanding to story form.

Who was "The Iron Horse of Baseball"? In fifth grade we were playing King of the Hill in class one Friday. I was in the hot seat, and had been for a long time, when Bobby Bergman, the most gorgeous boy in the whole elementary school, raised his hand, drilled me with his blue, blue eyes, asked me that question. I had just finished a biography of this guy and knew the answer as well as I knew my own name. Somehow the gaze from those eyes dried my throat up like the Sahara and my brain as well, and I just sat there with my mouth gaping open while Bobby Bergman took my chair. 50 years later it is still one of the great humiliations of my life.

Which brings me in a roundabout way to Philomena's poem about going to blackboard and besting some bright boy with a right answer a girl should not know. It was a good statement about audience which needed some tweaking. Mark made an appropriate remark about the ability to go "pfft" - he had better sound effects - at the not good stuff and lose it when you need to. Oh, yeah, Philomena's artwork is still in my office from the exhibit, and the Iron Horse was Lou Gehrig.

Mark's poem had my best line of the night: "opening great veins and white rivers to its soul. " He then taught us the typography tip of squinting your eyes at a page of text and finding the white rivers. I loved it.

We talked a little about Paul's habit of writing with no stanza breaks. Generally his work is short (this one is 19 lines) and so economical with words that there is no need for breaks. The topic of junk spurred some conversation and the suggestion that the title might be changed to Junkman instead of Junkyard as it was really a character study of the man not the location.

Joyce broke my heart with Life Measured in Cat Time, which was Cleo's obituary. Very nicely done. It was rather like prose written in poetic sentences and our only suggestion was to try a rewrite into a more traditional poem form.

Larry's Confessional Poem is walking away with My Favorite of the Night. It was laden with unacceptable-in-polite-society language and references, but totally, hysterically funny and I love it. I had no poem, having been embracing my arty self recently. Alan had no poem because he misunderstood the directions.

At the beginning of the meeting, we exchanged our inspirational trinkets to write about for August 27. Tom and Larry both brought safety pins. What does that mean?

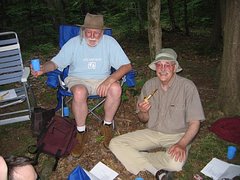

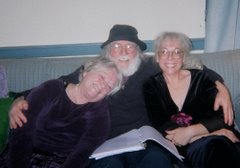

Here we are...

...a group of Baby Boomers of sundry religious,

political and cultural orientations, who have been

meeting at the Voorheesville Public Library since 1991

to read and discuss each other's poems.

We include old fathers and young grandmothers,

artists and musicians, and run-of-the-mill eccentrics.

Writers are welcome to stop in and stay if they like us.

political and cultural orientations, who have been

meeting at the Voorheesville Public Library since 1991

to read and discuss each other's poems.

We include old fathers and young grandmothers,

artists and musicians, and run-of-the-mill eccentrics.

Writers are welcome to stop in and stay if they like us.

Some of Us

Dennis Sullivan, Beverly Osborne, Tom Corrado, Edie Abrams, Art Willis, Alan Casline (all seated); Paul Amidon, Mike Burke, Tim Verhaegen, Mark O'Brien, Barbara Vink, Philomena Moriarty

Friday, July 24, 2009

Wednesday, July 15, 2009

More from Dennis

Many thanks to those who responded to “Giving Voice to the Vatic.” I will add one note in appreciation.

Always-thoughtful Larry is right in that a poetry group might benefit from thinking about poetry sometimes, and all that that entails. In the Voorheesville group we tried that once—instigated by me—and, for my money, it did not fare well. I still remember the angry and exclusionary remarks most.

I am appreciative of Tim’s enthusiasm and his telephone call to discuss briefly the monograph—I did make a very pretty [sic] monograph of the tractatus and sent it to some folks for review [limited edition of 25]—a very comely pic of the Sneem River in Sneem, Co Kerry, whence one side of the O’Sullivans hails, on the cover.

But I might point out that the statement that I made about poetry is filled with maybe 100 assumptions beginning in the first paragraph and going to the last.

For example, in paragraph one: in what way is the poetic tradition vatic and in what way is poetry a pracitce of the body; which suggests questions about how the body might be related to the imagination. And then a practice that begins WITH but DOES NOT END in death!

This kind of statement suggests that poetry has the power of a religion; can poetry transcend death? It might begin with the death of the beautiful but to say that it can put us in the mind/body of the beautiful and forever, that is a mighty big statement that I would not swallow so quickly. Though I have said that that is my ever-present aim—is to live in poetic consciousness always. It is where I am, feel happiest.

And in the last paragraph, for another example, w/r/t “the construction of self,” is the “self” constructed? Is life constructed? And if life is constructed, can it be constructed or in some way affected through the poem—but I had spoken earlier in the essay of how I viewed the poem.

Then it says: what can we ask of the poet? Well, anything? Allen Ginsberg always said the poet has no fixed role, so don’t go laying expectations on the poet—so what can we ask of the poet, the poem then? To bandage wounds!!! Some folks would say bullshit to that, thus I raise the question of: if we do that, do we hobble the poet, the poem?

My answer is yes, I say “more than likely” we would. But I add that poetry, the poet, the poem, is not about bandaging, anything, but about preventing. But preventing what? Like a police officer on patrol preventing street crime? Poets’d say they got better things to do.

I do not say so directly, but I say so, that poetry, through its affiliation with silence perhaps, prevents blows from being thrown that later require bandaging, that poetry structurally, through the power of imagination, prevents acts of violence—like death?—the kind of life designed to take us away from truth and beauty and enjoying the gift of life, that is, poetic consciousness?

Again for my money, anyone who reads and meditates on Wallace Stevens’ poem “The Snow Man,” [see below] for example—I can’t but think that she/he would be hard pressed to raise a hand at another in anger, the thought of a blow struck emptied of its vim, rather the spirit in openness.

The Snow Man

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

As you see, we could go on. This is all I will say here re: the comments and the essay. Thank you to those who responded, especially to Tim and Larry.

And I did send out an erratum page saying—for the monograph—page 2, para 2, line 1, for “Dickerson” read “Dickinson.”

Sincerely,

Dennis

Always-thoughtful Larry is right in that a poetry group might benefit from thinking about poetry sometimes, and all that that entails. In the Voorheesville group we tried that once—instigated by me—and, for my money, it did not fare well. I still remember the angry and exclusionary remarks most.

I am appreciative of Tim’s enthusiasm and his telephone call to discuss briefly the monograph—I did make a very pretty [sic] monograph of the tractatus and sent it to some folks for review [limited edition of 25]—a very comely pic of the Sneem River in Sneem, Co Kerry, whence one side of the O’Sullivans hails, on the cover.

But I might point out that the statement that I made about poetry is filled with maybe 100 assumptions beginning in the first paragraph and going to the last.

For example, in paragraph one: in what way is the poetic tradition vatic and in what way is poetry a pracitce of the body; which suggests questions about how the body might be related to the imagination. And then a practice that begins WITH but DOES NOT END in death!

This kind of statement suggests that poetry has the power of a religion; can poetry transcend death? It might begin with the death of the beautiful but to say that it can put us in the mind/body of the beautiful and forever, that is a mighty big statement that I would not swallow so quickly. Though I have said that that is my ever-present aim—is to live in poetic consciousness always. It is where I am, feel happiest.

And in the last paragraph, for another example, w/r/t “the construction of self,” is the “self” constructed? Is life constructed? And if life is constructed, can it be constructed or in some way affected through the poem—but I had spoken earlier in the essay of how I viewed the poem.

Then it says: what can we ask of the poet? Well, anything? Allen Ginsberg always said the poet has no fixed role, so don’t go laying expectations on the poet—so what can we ask of the poet, the poem then? To bandage wounds!!! Some folks would say bullshit to that, thus I raise the question of: if we do that, do we hobble the poet, the poem?

My answer is yes, I say “more than likely” we would. But I add that poetry, the poet, the poem, is not about bandaging, anything, but about preventing. But preventing what? Like a police officer on patrol preventing street crime? Poets’d say they got better things to do.

I do not say so directly, but I say so, that poetry, through its affiliation with silence perhaps, prevents blows from being thrown that later require bandaging, that poetry structurally, through the power of imagination, prevents acts of violence—like death?—the kind of life designed to take us away from truth and beauty and enjoying the gift of life, that is, poetic consciousness?

Again for my money, anyone who reads and meditates on Wallace Stevens’ poem “The Snow Man,” [see below] for example—I can’t but think that she/he would be hard pressed to raise a hand at another in anger, the thought of a blow struck emptied of its vim, rather the spirit in openness.

The Snow Man

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

As you see, we could go on. This is all I will say here re: the comments and the essay. Thank you to those who responded, especially to Tim and Larry.

And I did send out an erratum page saying—for the monograph—page 2, para 2, line 1, for “Dickerson” read “Dickinson.”

Sincerely,

Dennis

Tuesday, July 14, 2009

There are some excellent responses being posted to Dennis' remarks. Check them out and add your own.

bv

bv

Monday, July 13, 2009

THE DOLLAR STORE SUMMER TOUR

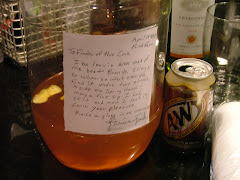

An email from Dan Wilcox led me to suggest a writing exercise which everyone seemed to like. So, you have an assignment for the next meeting: Bring an object from home to lend to another writer for a month's inspiration. We will exchange items at the next meeting and write about them. You can include it in a poem or devote a whole poem to it. Try and be creative when picking the object to bring in, and don't bring something you will need before the month is up.

I didn't take many notes at the last meeting, so this blog will be skimpy. I passed out new member lists. The mistake on this one is that Rachael's email needs an "e" added after rach. Please add it. I also passed around an article from the Schen Gazette about Art Willis (not as poet, but town historian). Nice photo.

Alan says there is still available space at the Aery for Obie's scheduled reading on July 13.

Call Alan at 475-7781.

I brought in a painting for Alan to take to the Pine Hollow arboretum art show. Several of us will be there on July 19 between 2 - 5. Stop by.

We welcomed absent Joyce who appeared with a poem dedicated to her mom and grandmother. It was accompanied by a great quote from Adrienne Rich: Until a strong line of love, confirmation and example stretches from mother to daughter, from woman to woman across the generations, women will still be wandering in the wilderness. Joyce did some re-writing on her poem with Alan's guidance.

Sticking with the women, Edie's poem told a wonderful story about a woman liberated by the death of her husband. Most of us were confused by the title "I met my mother at 42", but that is easily fixed. Rachael's "Question With No Answer" left me still questioning, but everybody else got it. Duh.

My own personal ton of bricks fell on Mike Burke (instead of poor Bird, for a change). He wrote about the demise of a local roadhouse and our picnic at his camp. Great beginning but I thought the second stanza was a big disappointment.

Larry wrote a clever piece about STUPID SHEWS which I was trying to call dialect but others preferred to refer to as "word play". Obeeduid was his new self again with a descriptive (and aromatic) work about remembered childhood - "there being no hedge or fence 'round time".

A small argument ensued over Paul's poem "The Old Ones" about be able to see a negative, which I couldn't see (is that a pun?). I guess I lost.

Tim was a big success for his couplets and the accompanying photo which totally made the whole poem. Not for the children, as it was of an adult nature, but effectively so.

I was happy with my "Felling The Willow" (no, not the willow at the pond, one of several others. Did you know that you could stick a willow twig in the ground and it will grow into a monstrous tree with only nature's assistance? ) - "they wrapped the giant in chains and beheaded it". Paul didn't like my semi-colons. (Paul just corrected me via comments: it was Alan who didn't like the semi-colons and Paul gave me a nice compliment on the poem. Thanks, Paul)

There follows this blog a rather lengthy guest post from Dennis, preceded by an intro to it. It was prompted by recent comments about the value of self-publishing. I have a much shorter answer, which I will keep to myself. Please respond to Dennis' article in the comments so we can all hear them. He has obviously given this serious thought.

I didn't take many notes at the last meeting, so this blog will be skimpy. I passed out new member lists. The mistake on this one is that Rachael's email needs an "e" added after rach. Please add it. I also passed around an article from the Schen Gazette about Art Willis (not as poet, but town historian). Nice photo.

Alan says there is still available space at the Aery for Obie's scheduled reading on July 13.

Call Alan at 475-7781.

I brought in a painting for Alan to take to the Pine Hollow arboretum art show. Several of us will be there on July 19 between 2 - 5. Stop by.

We welcomed absent Joyce who appeared with a poem dedicated to her mom and grandmother. It was accompanied by a great quote from Adrienne Rich: Until a strong line of love, confirmation and example stretches from mother to daughter, from woman to woman across the generations, women will still be wandering in the wilderness. Joyce did some re-writing on her poem with Alan's guidance.

Sticking with the women, Edie's poem told a wonderful story about a woman liberated by the death of her husband. Most of us were confused by the title "I met my mother at 42", but that is easily fixed. Rachael's "Question With No Answer" left me still questioning, but everybody else got it. Duh.

My own personal ton of bricks fell on Mike Burke (instead of poor Bird, for a change). He wrote about the demise of a local roadhouse and our picnic at his camp. Great beginning but I thought the second stanza was a big disappointment.

Larry wrote a clever piece about STUPID SHEWS which I was trying to call dialect but others preferred to refer to as "word play". Obeeduid was his new self again with a descriptive (and aromatic) work about remembered childhood - "there being no hedge or fence 'round time".

A small argument ensued over Paul's poem "The Old Ones" about be able to see a negative, which I couldn't see (is that a pun?). I guess I lost.

Tim was a big success for his couplets and the accompanying photo which totally made the whole poem. Not for the children, as it was of an adult nature, but effectively so.

I was happy with my "Felling The Willow" (no, not the willow at the pond, one of several others. Did you know that you could stick a willow twig in the ground and it will grow into a monstrous tree with only nature's assistance? ) - "they wrapped the giant in chains and beheaded it". Paul didn't like my semi-colons. (Paul just corrected me via comments: it was Alan who didn't like the semi-colons and Paul gave me a nice compliment on the poem. Thanks, Paul)

There follows this blog a rather lengthy guest post from Dennis, preceded by an intro to it. It was prompted by recent comments about the value of self-publishing. I have a much shorter answer, which I will keep to myself. Please respond to Dennis' article in the comments so we can all hear them. He has obviously given this serious thought.

Dear Poe-ettes,

For the past several years, at our Thursday group, open mics, and at social gatherings of poets in our region, I have heard a sizable number of poets speak about

the value of self-published work or work published by local publishers.

In private and in public some folks have been quite vocal about this matter, remarking on the large number of such publications some poets in the area have. I even heard several people raise questions about the little confab of local publishers held at UAG [I think it was] last year, where local presses “showed off” their work.

In response to questions, statements sent my way directly or indirectly, I told some folks in our Thursday group and elswhere that I wanted to think about the matter a bit. When I was in Ireland last March I sat down one day and wrote the following notes.

These notes address not only this matter but also the qualities of some small poetry groups and, maybe more importantly, what it means to be a poet, what the poem is [its purpose], and several other items of interest—or disinterest depending on one’s own interests. The nature of the poem, its purpose, and limitations and who or what a poet is I think are worthy of discussion.

Anyway, I share what I wrote, having just finished typing it up a few days ago. The Irish in me!

I put the essay into a little booklet as well, a very, very limited edition with a picture of the beautiful Sneem River on the cover; it runs through one of my home towns. Hopefully the notes will facilitate some reflection about the ideas, if they are of any value to anyone other than myself. I am happy with my part in the process regardless.

I will not discuss the matter through e-mail if there are responses to the thoughts here—I just cannot type that much in response—but will be happy to read what folks add to the blog and to discuss such matters face-to-face when I meet poets in the future.

I hope the writing of everyone progresses well.

Sincerely,

Dennis

For the past several years, at our Thursday group, open mics, and at social gatherings of poets in our region, I have heard a sizable number of poets speak about

the value of self-published work or work published by local publishers.

In private and in public some folks have been quite vocal about this matter, remarking on the large number of such publications some poets in the area have. I even heard several people raise questions about the little confab of local publishers held at UAG [I think it was] last year, where local presses “showed off” their work.

In response to questions, statements sent my way directly or indirectly, I told some folks in our Thursday group and elswhere that I wanted to think about the matter a bit. When I was in Ireland last March I sat down one day and wrote the following notes.

These notes address not only this matter but also the qualities of some small poetry groups and, maybe more importantly, what it means to be a poet, what the poem is [its purpose], and several other items of interest—or disinterest depending on one’s own interests. The nature of the poem, its purpose, and limitations and who or what a poet is I think are worthy of discussion.

Anyway, I share what I wrote, having just finished typing it up a few days ago. The Irish in me!

I put the essay into a little booklet as well, a very, very limited edition with a picture of the beautiful Sneem River on the cover; it runs through one of my home towns. Hopefully the notes will facilitate some reflection about the ideas, if they are of any value to anyone other than myself. I am happy with my part in the process regardless.

I will not discuss the matter through e-mail if there are responses to the thoughts here—I just cannot type that much in response—but will be happy to read what folks add to the blog and to discuss such matters face-to-face when I meet poets in the future.

I hope the writing of everyone progresses well.

Sincerely,

Dennis

Giving Voice to the Vatic:

The Poet and Locality

by

Dennis Sullivan

The poetic tradition is vatic, a tradition of vision and prophesy, and thus a practice of the body beginning with but not ending in death.

Poetry begins with the breakdown of boundaries, with cracks in the wall, where light pours in, filling the soul to overflowing. The poet is born in the person who sings ecstatic: “Rock o'my soul in de bosom of Abraham!”

While prose may be poetic, it is comprised of the leftovers of vatic chants, the construction of stories about before, during, and after, and is essentially, in construction of the flood—the how we fare, hope to fare, and fear we may not fare—narrative, though of course there is narrative poetry, poetry at its weakest link. This despite the assessment that all poetry is at heart narrative.

Regardless, not because of the poet’s intentions (poetry has no ax to grind) but because of how the light (lightening) strikes, the poem is a shared space in which all comers can speak about their dreams, every ilk and permutation. The poem, even though poets personally are not necessarily so, is truly democratic, anarchic, an oracle with structure but not necessarily logic, the farthest thing from linear, hence the remarks about narrative.

Poets do not choose to speak but are carried away by the flow or flash of light, a bacchanalian rite, the value of the poet and any particular poem being her/his/its drawing attention to the unsettling of the old and the creation of the new thereby engendering appreciation for life, the expressional joy of being alive, followed by steps to create, re-create that life anew. The poet is a personal demonstration project; look at Denise Levertov shining her light within a cave.

The publication of the poem then is not the poem (like you see in the store); the poem is the felt-expressed experience of new light, life, but the handing down of vatic praise, chant, warning, ecstatic babble, is made sense of only with great difficulty. There are some who worry about the audience of a poem which is foolishness at its core because the poet is the audience, the taker-in of the experience; the written-down or orally-transmitted expression of that experience is the after-thought of the poetic-act or after-act of poetic-thought, if you like.

There are some creatures who worry about the means by which the felt-expressed finds the light of day, its market value and distribution properties—it is a frame of mind—and thus are drawn from entering the sacred (I use this term with great trepidation and all due apology to anarchists, i. e., poets) and thus are drawn away from entering into the sacred space of the published poem and discovering or discovering anew their own life within it, life within.

How many poems did Emily Dickerson see published in her (bodily) lifetime but she was the living presence of poetry throughout it. In the early Christian church bishops (επίσκοποi) rose out of the commons; the community recognized what they had to say as vatic, prophetic, as having to do with the continuing life of community, the conditions of life and took the liberty to make that life public.

Vates were selected to minister, serve, the needs of community, to help the community understand and identify those needs and steps to take to meet them, acts that violated neither the individual nor collective will, through which the community of persons expressed its commitment to mutual aid, cooperation, love, selflessness, reconciliation, any quality or practice (both means and ends) that fostered the survival and enjoyable well-being of life.

Within the context of the poetic community—which is a contradiction in terms because the poet is a person of the whole community—vatic souls join together to understand the vatic experience and ways to keep it pure as possible, the least self-seeking. But a community that refuses to hieraticize itself (despite hieratic involvement) tends to lord it over the larger community thereby creating a rabblish poloi—the poet, the poem is there to dismantle, eradicate disable distinctions, not an aim but as a result of felt-lightening.

There arises at times within the community (large or small) individuals who give their lives to making public, giving voice to, the words, expressions, experiences regarding the lifeline-light (sometimes at the most local of local levels, where this all starts) giving voice to the vatic experience. Those who jump into this stream are not eagle eyes but eagle hearts and ears, “Look, the light! I will tell it on the mountain!” When John Work penned "Go tell it on the mountain, over the hills and everywhere" he was telling how the community had been struck by lightening anew.

The publisher, the making public-er, becomes a mountain (socialist soapbox) from which the vatic experience can be expressed and heard—a benevolent act—leaving it to the listener to decide: life-affirming or not? Those who go to the mountain to give voice, though connected to the market, sell wares of collectivity. The manufacture, sale, and distribution of poems are tied to the interests, needs, concerns, hopes, and fears of the community. Poets, like life itself, want life to continue and so aspire to mountaintops from which to speak the delight of experience, Rilke’s under any circumstances, “I praise!”

Big book little book, pamphlet, broadside tacked to the side of a bare-wood barn—no difference, the format immaterial to the felt-experienced-expressed word/poet of life. Essential is what the reader/listener/other-feeler experiences. Are they alive to the life-force, maybe moved to build a mountain to proclaim life from a peak themselves, become poets themselves.

Little poetry groups, workgroups, and the like, exist ad infinitum and, regardless of stated aims and purposes, sometimes stand in the way of life, ordaining themselves with rites that are solely self-directed. Their interest may be seeing poems published—with which there is no intrinsic problem—but sometimes (I’d like to see a study) the group stands in the way of the light seen.

There is nothing wrong with having a night out—who’s to say?—in the interest of sociality (a good 19th century moniker) and conviviality with seemingly like-minded persons (however measured) that is, persons interested in words, human expression, the appreciation of read and published poems and the implications of same for, well, we already said for what, but the “aim” is well worth exploring.

That is, the question persists: to what extent is a person in a work/study group and the group as a whole (its stated and practiced purpose) committed to understanding and appreciating (valuing) the vatic enterprise, which includes making known other vatic experiences that tell the truth (of life, of life’s requirements, human needs, survival, joy at the realization of the gift of life, etc.).

As stated, there are indeed judges and assessors of the truthful experience high and low. A publisher works with works regarded as reflecting the true vatic experience and fostering vividness in others. Who’s to say that person should not engage in joy, gratitude, and appreciation? Who’s to say only corporate/market-certified work is the truest or true reflection of life-engendering vatic experience, that capital credentials bolster the validity of the felt-experience?

While assessment of the vatic experience that leads to publication is welcome at all levels—welcomed or not it will take place—it is the community, the individuals within the community who are the ultimate and paradoxically the first-level assessors. Do we worry less, issue wistful sighs, covet relaxation? By reading, listening to, studying, explicating, divining, digging into, even with a pick ax, the experimenter is more alive, more connected, feels driven to share life with others or, at the very least, not deprive others of that experience—which includes slamming non-market-certified publishers from engaging in publicizing.

I might add that, while the vatic experience is ecstatic in nature, over which one, the poet, has no control (being hit with lightening is as good as any definition of being called) the poet has techniques, methods, structures, which clear away the debris which inserts itself into the light, so poems can remain as clear as first experienced. There is no such thing as “polishing” a poem—God forbid!—only opening up—whatever that is, that is a treatise in itself—to the originally-experienced inspiration, breath, light, spirit, from which the words, chant, poem, song, arose.

This is a process in which the poet tries to get out of the way of the prophetic experience. The felt-joy of the experience is too great to compromise through meddling, joined by a rabid fear that dissembling will lead to a loss of joy. Cynics will say the poet is engaging in a kind of hexing, in magical skullduggery—“The bard of Thrace drew the trees, held beasts enthralled and constrained stones to follow him” Metamorphoses XI, 1-2—but such statements are a projection of ill-seated paranoia and hucksterism, a disbelief in one’s own essential light to make an informed assessment of: am I alive? Let me count the ways. Is your math the same?

Thus the vates, called, chosen, wishes to be true to the vatic/prophetic. Of course the poet wishes her or his work known and when self-interest plays a role in the enterprise, we speak of true vates and false vates, true prophets and false prophets. The Greek Scriptures say it all: by our poetry we know our true selves; the effects of the practices preached tell the magicians, hucksters, tricksters from the healers, those who stack the deck versus those who bandage wounds.

In the construction of self, the construction of life in the form of the poem, the poet . . . well, is it too much to ask a poet to bandage wounds, does that not lame art at the outset—more than likely—but poetry is not about bandaging anything, it’s about preventing before the thought of a blow is struck.

The Poet and Locality

by

Dennis Sullivan

The poetic tradition is vatic, a tradition of vision and prophesy, and thus a practice of the body beginning with but not ending in death.

Poetry begins with the breakdown of boundaries, with cracks in the wall, where light pours in, filling the soul to overflowing. The poet is born in the person who sings ecstatic: “Rock o'my soul in de bosom of Abraham!”

While prose may be poetic, it is comprised of the leftovers of vatic chants, the construction of stories about before, during, and after, and is essentially, in construction of the flood—the how we fare, hope to fare, and fear we may not fare—narrative, though of course there is narrative poetry, poetry at its weakest link. This despite the assessment that all poetry is at heart narrative.

Regardless, not because of the poet’s intentions (poetry has no ax to grind) but because of how the light (lightening) strikes, the poem is a shared space in which all comers can speak about their dreams, every ilk and permutation. The poem, even though poets personally are not necessarily so, is truly democratic, anarchic, an oracle with structure but not necessarily logic, the farthest thing from linear, hence the remarks about narrative.

Poets do not choose to speak but are carried away by the flow or flash of light, a bacchanalian rite, the value of the poet and any particular poem being her/his/its drawing attention to the unsettling of the old and the creation of the new thereby engendering appreciation for life, the expressional joy of being alive, followed by steps to create, re-create that life anew. The poet is a personal demonstration project; look at Denise Levertov shining her light within a cave.

The publication of the poem then is not the poem (like you see in the store); the poem is the felt-expressed experience of new light, life, but the handing down of vatic praise, chant, warning, ecstatic babble, is made sense of only with great difficulty. There are some who worry about the audience of a poem which is foolishness at its core because the poet is the audience, the taker-in of the experience; the written-down or orally-transmitted expression of that experience is the after-thought of the poetic-act or after-act of poetic-thought, if you like.

There are some creatures who worry about the means by which the felt-expressed finds the light of day, its market value and distribution properties—it is a frame of mind—and thus are drawn from entering the sacred (I use this term with great trepidation and all due apology to anarchists, i. e., poets) and thus are drawn away from entering into the sacred space of the published poem and discovering or discovering anew their own life within it, life within.

How many poems did Emily Dickerson see published in her (bodily) lifetime but she was the living presence of poetry throughout it. In the early Christian church bishops (επίσκοποi) rose out of the commons; the community recognized what they had to say as vatic, prophetic, as having to do with the continuing life of community, the conditions of life and took the liberty to make that life public.

Vates were selected to minister, serve, the needs of community, to help the community understand and identify those needs and steps to take to meet them, acts that violated neither the individual nor collective will, through which the community of persons expressed its commitment to mutual aid, cooperation, love, selflessness, reconciliation, any quality or practice (both means and ends) that fostered the survival and enjoyable well-being of life.

Within the context of the poetic community—which is a contradiction in terms because the poet is a person of the whole community—vatic souls join together to understand the vatic experience and ways to keep it pure as possible, the least self-seeking. But a community that refuses to hieraticize itself (despite hieratic involvement) tends to lord it over the larger community thereby creating a rabblish poloi—the poet, the poem is there to dismantle, eradicate disable distinctions, not an aim but as a result of felt-lightening.

There arises at times within the community (large or small) individuals who give their lives to making public, giving voice to, the words, expressions, experiences regarding the lifeline-light (sometimes at the most local of local levels, where this all starts) giving voice to the vatic experience. Those who jump into this stream are not eagle eyes but eagle hearts and ears, “Look, the light! I will tell it on the mountain!” When John Work penned "Go tell it on the mountain, over the hills and everywhere" he was telling how the community had been struck by lightening anew.

The publisher, the making public-er, becomes a mountain (socialist soapbox) from which the vatic experience can be expressed and heard—a benevolent act—leaving it to the listener to decide: life-affirming or not? Those who go to the mountain to give voice, though connected to the market, sell wares of collectivity. The manufacture, sale, and distribution of poems are tied to the interests, needs, concerns, hopes, and fears of the community. Poets, like life itself, want life to continue and so aspire to mountaintops from which to speak the delight of experience, Rilke’s under any circumstances, “I praise!”

Big book little book, pamphlet, broadside tacked to the side of a bare-wood barn—no difference, the format immaterial to the felt-experienced-expressed word/poet of life. Essential is what the reader/listener/other-feeler experiences. Are they alive to the life-force, maybe moved to build a mountain to proclaim life from a peak themselves, become poets themselves.

Little poetry groups, workgroups, and the like, exist ad infinitum and, regardless of stated aims and purposes, sometimes stand in the way of life, ordaining themselves with rites that are solely self-directed. Their interest may be seeing poems published—with which there is no intrinsic problem—but sometimes (I’d like to see a study) the group stands in the way of the light seen.

There is nothing wrong with having a night out—who’s to say?—in the interest of sociality (a good 19th century moniker) and conviviality with seemingly like-minded persons (however measured) that is, persons interested in words, human expression, the appreciation of read and published poems and the implications of same for, well, we already said for what, but the “aim” is well worth exploring.

That is, the question persists: to what extent is a person in a work/study group and the group as a whole (its stated and practiced purpose) committed to understanding and appreciating (valuing) the vatic enterprise, which includes making known other vatic experiences that tell the truth (of life, of life’s requirements, human needs, survival, joy at the realization of the gift of life, etc.).

As stated, there are indeed judges and assessors of the truthful experience high and low. A publisher works with works regarded as reflecting the true vatic experience and fostering vividness in others. Who’s to say that person should not engage in joy, gratitude, and appreciation? Who’s to say only corporate/market-certified work is the truest or true reflection of life-engendering vatic experience, that capital credentials bolster the validity of the felt-experience?

While assessment of the vatic experience that leads to publication is welcome at all levels—welcomed or not it will take place—it is the community, the individuals within the community who are the ultimate and paradoxically the first-level assessors. Do we worry less, issue wistful sighs, covet relaxation? By reading, listening to, studying, explicating, divining, digging into, even with a pick ax, the experimenter is more alive, more connected, feels driven to share life with others or, at the very least, not deprive others of that experience—which includes slamming non-market-certified publishers from engaging in publicizing.

I might add that, while the vatic experience is ecstatic in nature, over which one, the poet, has no control (being hit with lightening is as good as any definition of being called) the poet has techniques, methods, structures, which clear away the debris which inserts itself into the light, so poems can remain as clear as first experienced. There is no such thing as “polishing” a poem—God forbid!—only opening up—whatever that is, that is a treatise in itself—to the originally-experienced inspiration, breath, light, spirit, from which the words, chant, poem, song, arose.

This is a process in which the poet tries to get out of the way of the prophetic experience. The felt-joy of the experience is too great to compromise through meddling, joined by a rabid fear that dissembling will lead to a loss of joy. Cynics will say the poet is engaging in a kind of hexing, in magical skullduggery—“The bard of Thrace drew the trees, held beasts enthralled and constrained stones to follow him” Metamorphoses XI, 1-2—but such statements are a projection of ill-seated paranoia and hucksterism, a disbelief in one’s own essential light to make an informed assessment of: am I alive? Let me count the ways. Is your math the same?

Thus the vates, called, chosen, wishes to be true to the vatic/prophetic. Of course the poet wishes her or his work known and when self-interest plays a role in the enterprise, we speak of true vates and false vates, true prophets and false prophets. The Greek Scriptures say it all: by our poetry we know our true selves; the effects of the practices preached tell the magicians, hucksters, tricksters from the healers, those who stack the deck versus those who bandage wounds.

In the construction of self, the construction of life in the form of the poem, the poet . . . well, is it too much to ask a poet to bandage wounds, does that not lame art at the outset—more than likely—but poetry is not about bandaging anything, it’s about preventing before the thought of a blow is struck.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)