Many thanks to those who responded to “Giving Voice to the Vatic.” I will add one note in appreciation.

Always-thoughtful Larry is right in that a poetry group might benefit from thinking about poetry sometimes, and all that that entails. In the Voorheesville group we tried that once—instigated by me—and, for my money, it did not fare well. I still remember the angry and exclusionary remarks most.

I am appreciative of Tim’s enthusiasm and his telephone call to discuss briefly the monograph—I did make a very pretty [sic] monograph of the tractatus and sent it to some folks for review [limited edition of 25]—a very comely pic of the Sneem River in Sneem, Co Kerry, whence one side of the O’Sullivans hails, on the cover.

But I might point out that the statement that I made about poetry is filled with maybe 100 assumptions beginning in the first paragraph and going to the last.

For example, in paragraph one: in what way is the poetic tradition vatic and in what way is poetry a pracitce of the body; which suggests questions about how the body might be related to the imagination. And then a practice that begins WITH but DOES NOT END in death!

This kind of statement suggests that poetry has the power of a religion; can poetry transcend death? It might begin with the death of the beautiful but to say that it can put us in the mind/body of the beautiful and forever, that is a mighty big statement that I would not swallow so quickly. Though I have said that that is my ever-present aim—is to live in poetic consciousness always. It is where I am, feel happiest.

And in the last paragraph, for another example, w/r/t “the construction of self,” is the “self” constructed? Is life constructed? And if life is constructed, can it be constructed or in some way affected through the poem—but I had spoken earlier in the essay of how I viewed the poem.

Then it says: what can we ask of the poet? Well, anything? Allen Ginsberg always said the poet has no fixed role, so don’t go laying expectations on the poet—so what can we ask of the poet, the poem then? To bandage wounds!!! Some folks would say bullshit to that, thus I raise the question of: if we do that, do we hobble the poet, the poem?

My answer is yes, I say “more than likely” we would. But I add that poetry, the poet, the poem, is not about bandaging, anything, but about preventing. But preventing what? Like a police officer on patrol preventing street crime? Poets’d say they got better things to do.

I do not say so directly, but I say so, that poetry, through its affiliation with silence perhaps, prevents blows from being thrown that later require bandaging, that poetry structurally, through the power of imagination, prevents acts of violence—like death?—the kind of life designed to take us away from truth and beauty and enjoying the gift of life, that is, poetic consciousness?

Again for my money, anyone who reads and meditates on Wallace Stevens’ poem “The Snow Man,” [see below] for example—I can’t but think that she/he would be hard pressed to raise a hand at another in anger, the thought of a blow struck emptied of its vim, rather the spirit in openness.

The Snow Man

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

As you see, we could go on. This is all I will say here re: the comments and the essay. Thank you to those who responded, especially to Tim and Larry.

And I did send out an erratum page saying—for the monograph—page 2, para 2, line 1, for “Dickerson” read “Dickinson.”

Sincerely,

Dennis

Here we are...

...a group of Baby Boomers of sundry religious,

political and cultural orientations, who have been

meeting at the Voorheesville Public Library since 1991

to read and discuss each other's poems.

We include old fathers and young grandmothers,

artists and musicians, and run-of-the-mill eccentrics.

Writers are welcome to stop in and stay if they like us.

political and cultural orientations, who have been

meeting at the Voorheesville Public Library since 1991

to read and discuss each other's poems.

We include old fathers and young grandmothers,

artists and musicians, and run-of-the-mill eccentrics.

Writers are welcome to stop in and stay if they like us.

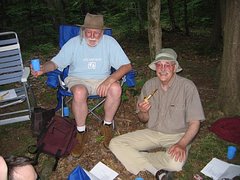

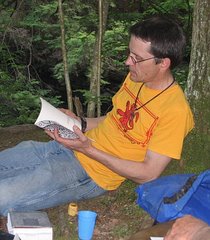

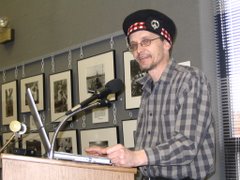

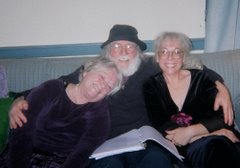

Some of Us

Dennis Sullivan, Beverly Osborne, Tom Corrado, Edie Abrams, Art Willis, Alan Casline (all seated); Paul Amidon, Mike Burke, Tim Verhaegen, Mark O'Brien, Barbara Vink, Philomena Moriarty

Wednesday, July 15, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment