DEAR POE-ETTES,

Tuesday August 17, 2010 6:40 am, The Ville

I see in this morning’s New York Times that Clint Eastwood has a new film “Hereafter” about to be shown at the New York Film Festival. In the film Eastwood tackles issues of death, near-death, and the so-called afterlife—a timely topic for many of us. For me in particular because I was going to recommend to you all this past week Helen Vendler’s newest book Last Looks, Last Books by Princeton University Press. I cannot recommend it strongly enough to poets interested in poetry.

The “last looks” part of the book refers to a supposed tradition of the Irish who, near death, go out amongst their favorite fields, etc. to get a last peek before they die. A kind of meet your maker. As in: this is who I was, this is who I am, this is the who who will shortly never be.

The “last books” part refers to poets who through their written work express their ideas, feelings, and general sentiments about their last looks. That is, what they say about death and how they try to make sense of their “passing” into whatever happens when we die. To say afterlife is to already have begged the question.

This grand dame of American letters at Harvard—she is as great one; Wikipedia reminds us that in 2004 the National Endowment for the Humanities selected her for the Jefferson Lecture, the highest honor for achievement in the humanities the United States government gives out—tackles the last books of Wallace Stevens, Sylvia Plath, Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, and James Merrill, five of my favorites. I mean how much has been said about Plath’s handing of her humanity and what death would do to enhance it.

Vendler says that poets—who work outside religious traditions such as Christianity and others religions which have packaged ideas about death and how to handle it in life—in effect have to create their own idioms and rituals through their making of poems. And those words are not icing on a cake, but a way a person/poet can pass into an unknown that is unimaginable, (or is it?) territory, a switch in consciousness, the off-switch. I could say more, let me just say I recommend it highly.

And, by the bye, I just got a note from Amazon that her Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries which was scheduled to come out in September will be out next week. I cannot wait to see her take on Emily. I recommend this as well, one grand dame examining the work of another American great. This is fireside reading.

W/r/t the first book of hers I mentioned here on last looks, I was reminded of a piece that Peter Brown wrote in The New York Review of Books in 2008 “The Private Art of Early Christians” reviewing an exhibition at the Kimball Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. It made me want to live in Fort Worth for a day to see it. The exhibit lasted from November 2007 to March 2008.

Why I bring this piece up is that Brown points to the earliest remnants of Christian art from private homes which tell stories about life and dialectically death. There was a rather “secular” [not a word I use, not one that fits into my ideology, but I use it here because of this context] view of life and death. That is, the art did not reflect the theology and selling of Jesus as personal savior, especially when you die. See the Vendler connection? Poets do not sell anything, they try to figure out human dilemmas for the community, for the great collective.

Brown says one of the most “touching” pieces in the collection—and he sold me on it— was one “of the gold glass pieces (catalog pages 192–193) [showing] a classical shepherd surrounded by his sheep. Around the edge is written, “(Be) the pride of your friends. Drink. May you live! [in Greek] May you live! [added in Latin, just to be sure!]” A collective mentality, a carpe diem. Imagine being the pride of your friends, someone people have something nice to say about—and not after you die!

That is, there was a modestly human basis to the art that grew out of experience, not a superimposed theology as we think of today. Important Catholic art historians put a religious spin on every social event they examined in art, a woman praying had to be the first nun, a woman and child eating a picnic lunch had to be Many and Jesus with the Eucharist.

When my aunt died a few weeks ago and I went to Staten Island to attend her wake and funeral, at the funeral mass the priest said that through Jesus she will live forever, that she has been resurrected, that she had not died in Jesus. I thought: what a religion, you think he might have thrown her a few more months while she was alive! That I’d sign up for for it has a very human grounding.

Brown says in the Fort Worth exhibition, “Two rooms later, in the last part of the exhibition, [as the centuries have moved on] we see the ultimate symbol of Christ’s power at its fullest development—a fragment of the Cross itself placed in a cross of gold studded with gems, given to Rome by the emperor Justin II sometime between 568 and 574 (catalog pages 283–285; see illustration on page 49 of this article). Glowing in the dark with barbaric splendor, this was still a Cross of victory. As the inscription made clear, this was the Cross on which Christ had “subdued [death] the enemy of mankind.” It was also a Cross calculated to keep human enemies (of which there were all too many by that time) away from the walls of Rome.”

Here we have the superimposition of a Christian poetry if you will on life, dictating how things go down in death and who is big enough to handle that death—there is only one. How does that help people make sense of their life and death in human terms, terms that can be understood by others.

There is more I can say about this but you can see how Brown’s piece, the exhibit actually, fits in nicely with Vendler’s analysis of the poetic works of human beings through poetry trying to figure out how to be “victorious” in death, how to subdue it, and if not that, whatever. I have written any number or poems on death and life, all my poems reflecting the theology of Dennis Sullivan, with a foundation that I always hope others will see as valuable for them, in that they can develop a theology, a poetry that reflects their experience.

And to extend the analysis, how does poetry keep the enemies of self away from self so that one can achieve some level of peace of mind. This is what poetic consciousness does for me, a state of mind that is both creative and gratitudinously peaceful. How’s that for a start on a way to beat death? Poetic consciousness leads us out on a high note. For all the Snow Man Wallace Stevens is, I do not think he is bummed out, just weighed down by reality, but a reality that when understood brings a certain joy, one that helps face death sanely.

Finally, and to go back to Vendler again, her first subject in the last look books is Stevens, in particular his “The Plain Sense of Things,” pointing to Stevens saying that in a certain situation he is having a hard time picking an adjective to describe it—see the first line second stanza—to say what he wants to say “after the leaves have fallen,” hen one realizes that one’s time has come..

Here is his poem below. It is beautiful. I throw these things out today for your poetic enjoyment. Plus anyone who would like me to send them, via e-mail, a copy of the Brown piece—I do subscribe to The New York Review of Books, in print and online, my longest continuous subscription, over 30 years—I will be happy to do so.

Peace,

Dennis

================

Wallace Stevens (1879 –1955)

THE PLAIN SENSE OF THINGS

After the leaves have fallen, we return

To a plain sense of things. It is as if

We had come to an end of the imagination,

Inanimate in an inert savoir.

It is difficult even to choose the adjective

For this blank cold, this sadness without cause.

The great structure has become a minor house.

No turban walks across the lessened floors.

The greenhouse never so badly needed paint.

The chimney is fifty years old and slants to one side.

A fantastic effort has failed, a repetition

In a repetitiousness of men and flies.

Yet the absence of the imagination had

Itself to be imagined. The great pond,

The plain sense of it, without reflections, leaves,

Mud, water like dirty glass, expressing silence

Of a sort, silence of a rat come out to see,

The great pond and its waste of the lilies, all this

Had to be imagined as an inevitable knowledge,

Required, as necessity requires.

Here we are...

...a group of Baby Boomers of sundry religious,

political and cultural orientations, who have been

meeting at the Voorheesville Public Library since 1991

to read and discuss each other's poems.

We include old fathers and young grandmothers,

artists and musicians, and run-of-the-mill eccentrics.

Writers are welcome to stop in and stay if they like us.

political and cultural orientations, who have been

meeting at the Voorheesville Public Library since 1991

to read and discuss each other's poems.

We include old fathers and young grandmothers,

artists and musicians, and run-of-the-mill eccentrics.

Writers are welcome to stop in and stay if they like us.

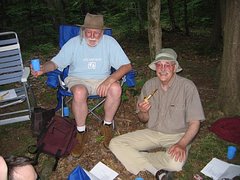

Some of Us

Dennis Sullivan, Beverly Osborne, Tom Corrado, Edie Abrams, Art Willis, Alan Casline (all seated); Paul Amidon, Mike Burke, Tim Verhaegen, Mark O'Brien, Barbara Vink, Philomena Moriarty

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Man proposes, God disposes..................................................................

ReplyDeleteIt is never too late to learn.......................................................................

ReplyDeleteTo Dennis: I've just finished reading "A Travel Guide to Heaven" by DiStefano, in which he says that heaven is just that...all our friends and relatives will greet us, as well as our favorite pet(s), and we can sight see, dinosaurs, talk with famous people: Abe Lincoln etc and have a great time, eat as much as we want, never sleep, no need for doctors or surgeons, or cars or insurance or taxes etc etc. I want to believe every word and hope he's right....Dan Lawlor

ReplyDelete